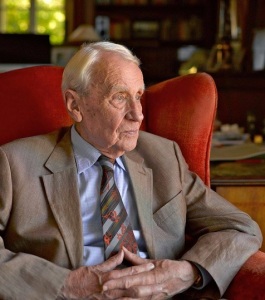

Hannah Long gives a well-deserved tribute to J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and literary heir Christopher in the latest Weekly Standard. Long’s introduction to Christopher Tolkien’s life work includes insights into what makes the elder Tolkien’s stories so enchanting and timeless.

Hannah Long gives a well-deserved tribute to J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and literary heir Christopher in the latest Weekly Standard. Long’s introduction to Christopher Tolkien’s life work includes insights into what makes the elder Tolkien’s stories so enchanting and timeless.

The junior Tolkien’s task was not easy: He had to organize, polish, and edit 70 boxes of manuscripts his father left behind, many stuffed with scraps of poetry, notes, and incomplete short stories. But out of that chaos, Christopher Tolkien harvested 25 works the world would probably never have seen otherwise, including The Silmarillion and a prose translation of Beowulf. The latest, The Fall of Gondolin, saw publication this August.

Tolkien’s works continue to nourish a reading public hungry for the myths that Tolkien made new, accessible, and meaningful. Tolkien and his fellow Inklings were rebels who waged literary war against the bleak alienation and scientism of their age. As Long puts it in her article:

For the Inklings, the medium of fantasy restored—or rather revealed—the enchantment of a disenchanted world. It reinstated an understanding of the transcendent that had been lost in postwar alienation.

“The value of myth,” C.S. Lewis wrote in an essay defending The Lord of the Rings, “is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by ‘the veil of familiarity.’” In this, fantasy did precisely the opposite of what its critics alleged—it did not represent a flight from the real world but a return to it, an unveiling of it. A child, Lewis wrote, “does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods,” but “the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”

And isn’t that what attracts us to fantasy fiction? Today, people find themselves in a blur of gadgets, images, and endless consumption that replaces, rather than enhances, human existence. The enduring appeal of the Inklings’ works, as with all good fantasy, is the astounding news that the enchanted dwells with us, that beauty and mystery surround and enrich us even when we’re too busy to notice.

A wonderful post about Tolkien and his importance to us all. There is so much in this article to comment on and facts that impresses. I also took delight in the quotes included.

Miriam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Miriam,

Tolkien’s work is an endless gold mine. I cannot conceive how he wrote it while working as a professor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps driven by a rare passion. I am now intrigued and will read up more about him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m saving this one. Love that last paragraph. Lately, I’ve become aware of how distracted I am. I think technology is rewiring my brain so I’m less perceptive. Not only do I fail to notice the late Visa bill next to my chair (doggonit), but it’s harder to see the pain behind a friend’s smile or detect the subtext in her words. But fantasy helps us see invisible reality, and maybe that carries over into our everyday lives. Maybe it’s a remedy for iphone-addiction dullness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

kakymc,

I don’t think the tech is intrinsically bad, but we don’t manage it as we should. We have to stay in control — if you’re checking your email every minute or walking and texting when you should be taking in the sights, the gadget’s controlling you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful post, Mike!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jennie,

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLike

Thanks for highlighting Tolkein’s work. I love this quote: A child, Lewis wrote, “does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods,” but “the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.” Just added it to my collection.

LikeLiked by 2 people

EvelynKrieger,

That’s my favorite quote from the article.

LikeLike

Greetings, Mike. I’ve heard the name Tolkien pronounced several ways. Do you know the correct pronunciation?

Neil

LikeLike

It’s “Toll” “Kin” with the accent on the first syllable.

LikeLike

Many thanks

LikeLike

I love the wrap-up in the last paragraph. So true. Fantasy offers a glimpse of the vast realm of the imagination where anything is possible and we are free to step outside of the mundane.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Diana,

Exactly! Fantasy fiction seeks to make the mundane magical again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We owe the younger Tolkien a debt of gratitude, as we do to the elder for setting a standard for fantasy writers ever since.

LikeLiked by 1 person

colonialist,

A standard few have equaled, by the way.

LikeLike

Indeed so. Or even come close.

Some notable exceptions don’t have the recognition they deserve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His work on his father’s manuscripts was indeed brilliant, but I couldn’t plow through his fiction. But he was indeed a born archivist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m incredibly grateful to Christopher Tolkien for all his hard work getting these stories to us. Also for The History of Middle-Earth series, which is a painstaking examination of the step-by-step creation of Lord of the Rings and other works. Reading these books, which must have taken forever to compile, has taught me important things about Tolkien’s writing process and helped me to better understand my own.

LikeLiked by 1 person