There’s no doubt in my mind that the modern world is an ill-fitting cage for its human captives. Basic needs for social interaction, exercise, and a sense of connection to the wider universe are left behind in a mad rush for consumption, mindless pleasure, and false security.

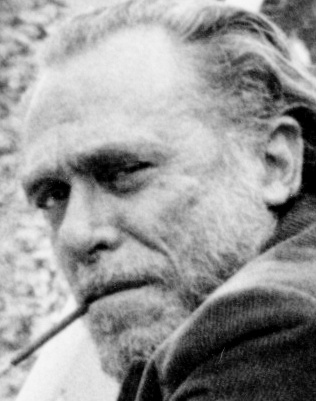

Our lemming-like pursuit of immediate gratification and “convenience” has cut us off from the most basic of human needs. Philosopher and author Romano Guardini identified this self-made disconnect as the source of the gnawing fears and doubts that plague modern existence:

Modern anxiety… arises from man’s deep-seated consciousness that he lacks either a ‘real’ or a symbolic place in reality. In spite of his actual position on earth he is a being without security. The very needs of man’s senses are left unsatisfied, since he has ceased to experience a world which guarantees him a place in the total scheme of existence.

James C. Scott, a political scientist and anthropologist at Yale, argues we’re in an Anthropocene Age, characterized by homo sapiens’ disproportionate influence on nature. That influence, says Scott, is not only harming other species, but our own as well. Scott’s main point is that we got ourselves and our fellow Earthlings in the fix we’re in when we started clustering around cities. Sadly, the comfort and security of cities and the nation-states they spawned was a cruel illusion. The hierarchies that profited from the creation and management of the nation-state increasingly demanded control over lives and property to perpetuate themselves. However, those ruling hierarchies were inherently unstable, often breeding foreign and domestic wars to impose or consolidate their power.

Richard Adrian Reese notes what was lost when hunter-gatherers surrendered to the forces of centralization:

Scott focused on southern Mesopotamia, because it was the birthplace of the earliest genuine states. What are states? They are hierarchical societies, with rulers and tax collectors, rooted in a mix of farming and herding. The primary food of almost every early state was wheat, barley, or rice. Taxes were paid with grain, which was easier to harvest, transport, and store than yams or breadfruit. States often had armies, defensive walls, palaces or ritual centers, slaves, and maybe a king or queen.

What to do? We can re-humanize ourselves by better understanding what our bodies and souls really need, and by modifying our lifestyles to meet those needs. The first step, however, is to open our eyes to the addictions that have enslaved us and realize there is a better way.