That unshaven bum is me on my back deck at Carolina Beach, armed with notebook, binoculars, and strong coffee. We’re SLOWLY transitioning to the beach, and on our last trip earlier this month, we really lucked up on the weather.

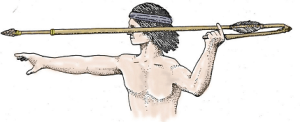

While my wife worked her real estate magic on the phone, I worked on a sword and sorcery story. Though I’ve long relished the works of Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, and Fritz Leiber, I’ve never before tried my hand at this genre. Of course, this calls for guerrilla-style research, from the history of the locale I’ve picked, to the tropes and traditions of sword and sorcery adventures.

Now that’s my idea of a good time.

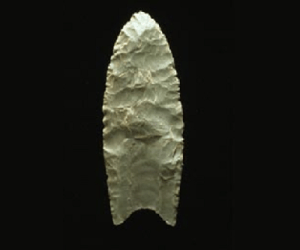

And while changing latitudes, I’m changing a few attitudes as well. I’ve always insisted on writing at my desk in crypt-like silence. But I’m learning to adapt and take advantage of writing opportunities as they come along. I wrote in the car on our way down, and, as you can see by the Mona-Lisa-like smile on my face, am getting the hang of composing by the sea shore. The hypnotic rhythm of the crashing waves seems to pull me forward, and I’m pleased with the manuscript. It has magic. It has knives. It has slings. And of course, desperate battles.

To get in the proper spirit the morning I wrote on the deck, I did Isshin-ryu katas for a half hour and then Julie and I took a long walk on the beach. I’ve long believed in the mutually reinforcing interplay of the body and the imagination. I like the way Nietzsche described how walking sparked creativity:

“We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors — walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea where even the trails become thoughtful.”

Thoughtful indeed. The sea, which has a role in my story, teems with history, wonder, and vivid spectacles of life and death. I think Freddy was on to something.