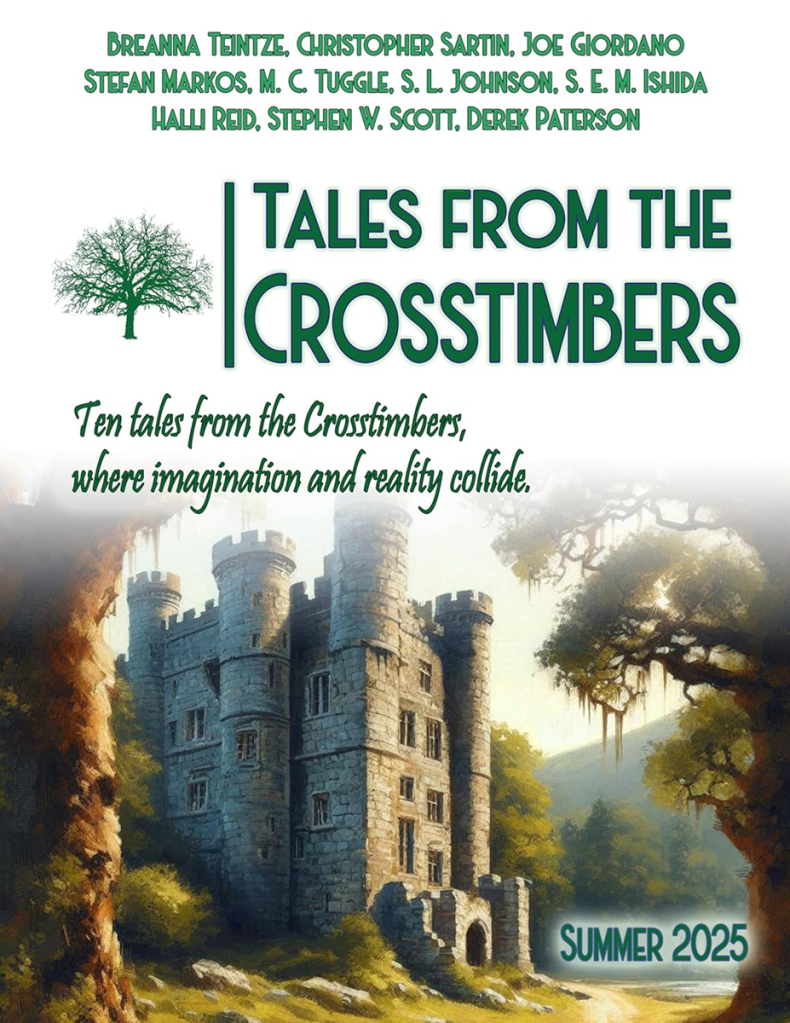

I’m pleased to announce that the winter issue of Tales from the Crosstimbers is now available on Amazon. It includes my story “At the Edge of the Crater.”

Jak, a newcomer to the mining colony on the asteroid 16 Psyche, ignores his partner’s warning not to travel alone into the asteroid’s Badlands. There’s a rich new vein of iridium to claim, and Jak wants first pick. All he has to do to win the race is to venture into a forbidding impact crater.

I wrote this tale as a futuristic version of “To Build a Fire” by Jack London. In “Crater,” the protagonist lets greed drown out the warnings of his more experienced partner. Space, like all of nature, often overwhelms us with its beauty and mystery but can also snuff out human life in an instant. To understand ourselves, and to grasp our place in the universe, we must realize we are mites compared to the limitless expanse of space. Survival is a struggle, one best waged with friends at our side.

Tales from the Crosstimbers features speculative tales “grounded in strong characters interacting with a gritty, realistic world.” So it’s the perfect venue for this story. I’m honored to be included with this line-up of authors.