I’ve signed a contract with Mystery Weekly Magazine, which will publish my novelette “Absence of Evidence” this winter. This is my second story with them, and I do believe I’ll be writing more crime fiction. This is fun.

Writing murder mysteries has reminded me of the importance of knowing the tools of the trade. Agatha Christie learned about poisons as a nurse in World War I, and drew on that knowledge to devise her delightfully macabre plots. Mickey Spillane, who’d served in World War II, used his knowledge of guns to add chills and gritty realism to his hardboiled yarns.

Growing up in the country, I spent a lot of time hunting, fishing, and backpacking. Like Clifton Clowers, I got to be mighty handy with a gun and a knife. Isshin-ryu karate introduced me to kobudo, the melee weapons techniques of Okinawan martial arts. Many of my fantasy stories feature both firearms and melee weapons. Knowing their uses and limitations makes the action more believable.

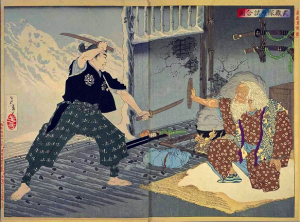

So from left to right in the above image, here are some of the most popular melee weapons (and their dirty secrets):

Knives don’t get the respect they deserve. Guns get all the attention. But knives never jam, never run out of ammo, and are ready when you are. A gun must have a round in its chamber, and you can’t fire it if you forget to turn off the safety. Also, a gun doesn’t always beat a knife. Once he’s about 25 feet from his target, a skilled knife fighter can swoop in and overwhelm a gunman before he can unholster. And every knife wound is potentially lethal.

The sai is another weapon people don’t properly respect. (Cue the theme song from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.) It may appear to be just for show, but it’s a real weapon. Okinawan police used it for centuries. Though it has sword-like wrist guards, a sai is really a baton. Sai techniques can be adapted to makeshift weapons, such as a heavy-duty screwdriver.

The tonfa is also a modified baton. The side handle allows a superior grip, which makes it an effective blocking weapon, and also prevents it from rolling away if dropped. But it’s also an excellent offensive weapon. The side handle enables a skilled user to whip the tonfa with bone-breaking power. Side-handled batons are standard issue in many police departments.

The nunchaku is one weapon that can do more harm to its user than the target. I’ve seen it happen. It’s easy to miscalculate the nunchaku’s lightning-fast arc, and if it strikes something solid, it can bounce back and rap your face or knuckles. I still practice nunchaku katas, but more for the discipline than practicality. And hey, it looks cool.

The standard baton (nightstick) is the most useful and reliable melee weapon. Anyone can pick one up and use it, but it’s especially potent in the hands of someone who knows its capabilities. A baton can be used in countless choking, restraining, and blocking techniques, as well as for good old-fashioned skull-cracking. And its high-tech cousin, the collapsible baton, is not only discrete, but can be quickly deployed, making it both handy and practical.

“All the great poets should have been fighters,” Muhammad Ali once said. “Take Keats and Shelley, for an example. They were pretty good poets, but they died young. You know why? Because they didn’t train.”

“All the great poets should have been fighters,” Muhammad Ali once said. “Take Keats and Shelley, for an example. They were pretty good poets, but they died young. You know why? Because they didn’t train.”