“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history.”

Rachel Carson

Sometimes otherwise smart people don’t stay in their lane. Trouble begins when they imagine they’ve discovered earth-shaking truths in fields unimagined by people trained in those fields. It’s called epistemic trespassing.

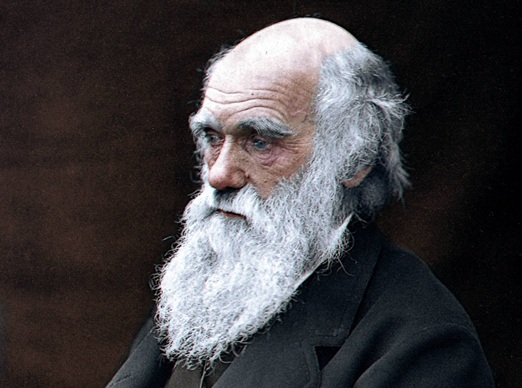

Ezra Pound revolutionized modern poetry but turned into a crank spouting bizarre economic theories. Linus Pauling won a Nobel Prize in chemistry before taking up quack medicine. Here’s the latest: Theodore Beale is an accomplished fantasy author who claims he’s destroyed Charles Darwin and natural selection. Writing under the name Vox Day, he’s released a book titled Probability Zero: The Mathematical Impossibility of Evolution by Natural Selection.

Here’s the description of his book from Amazon: “By subjecting the big ideas of Darwin, Haldane, Mayr, Kimura, and Dawkins to the pitiless light of statistical and mathematical analysis, Day demonstrates that the Modern Synthesis isn’t just flawed—it is absolutely impossible.”

And that’s it. Vox Day has made no ground-breaking research, no new discoveries, and offers no evidence from any science. He thinks he’s bypassed all that by claiming natural selection is so statistically improbable, it can be dismissed as impossible.

In other words, he only recycles the creationist “Junkyard tornado” argument that no scientific evidence can overcome the odds against life arising and developing naturally.

Okay. What would happen if we decided probability trumps evidence when making inquiries? I can “prove” it’s impossible my wife and I could have ever met and married. But a better example comes to mind.

Remember the horrific murder of Iryna Zarutska in Charlotte last August ? A lawyer could use statistics alone to shoot down the prosecution’s case against DeCarlos Brown Jr., who is accused of stabbing Zarutska on a late-night train.

Consider: Of the 8.3 billion people in the world, Brown allegedly murdered a woman born in Ukraine, 5,200 miles away. Every day on Earth, only 120 people are killed by strangers. That means the probability of a homeless man in Charlotte killing a woman from Ukraine is 0.00000144578313253 %. And since only 1.5 % of Charlotte residents use the light rail, the odds of Brown encountering and killing Zarutska would be reduced to practically nothing.

Should a jury ignore the so-called DNA and eyewitness evidence and let Brown roam the streets of Charlotte again? Hopefully, when DeCarlos Brown Jr. gets his day in court, the jury will judge him based on the evidence, which tells us that despite the odds, Zarutska was on that train when Brown killed her.

The theory of evolution is also backed by evidence–abundant evidence from many branches of science.

But here’s the kicker–Day doesn’t deny the evidence for evolution. He even cites an example of human evolution:

“The primary European lactase persistence allele (LCT-13910*T) is estimated to have arisen approximately 7,500–10,000 years ago, coinciding with the advent of dairying in Neolithic Europe. This mutation confers a significant nutritional advantage in cultures that practice animal husbandry, as it allows adults to digest milk—a rich source of calories, protein, fat, and calcium that would otherwise cause gastrointestinal distress” (p. 110).

If you’re puzzled, re-read the book’s subtitle: “The Mathematical Impossibility of Evolution by Natural Selection.” Creationists will be disappointed thinking the book is a refutation of evolution. So what is Day arguing? In the book’s foreword, Frank Tipler, a professor of mathematics, spells out its purpose: “Mr. Day will demonstrate that, since evolution cannot have occurred by unintended means, evolution must have been directed.” In other words, Day accepts the overwhelming evidence for evolution, but claims natural selection is not the cause.

Even though he doesn’t use the term, Day is arguing for Intelligent Design, a pseudoscience cobbled together as a front for creationism. ID emerged after the bad publicity following Edwards v. Aguillard, in which the Supreme Court ruled that teaching creationism is an unconstitutional attempt to establish a particular religion. While creationism argues that scripture justifies the belief that life was created by a divine being, ID co-opts large chunks of science in an attempt to assert some mysterious, unknown intelligence — maybe aliens! — created life. Day calls his version “Intelligent Genetic Manipulation.”

Like the old creationists, however, Day argues for a “First Mover” and “Designer” as the hidden driver of evolution and specifically posits the Abrahamic God as its guiding force. Addressing the argument that structural defects — the eye’s blind spots, for example — disprove intelligent design, Day offers this totally scientific explanation:

“perhaps demons might manipulate genetics in opposition to it, or for purposes of their own that align with neither divine nor human interests. This could explain certain puzzling features of biological design: not mere suboptimality, but apparent malevolence. Why do parasites exist that can only reproduce by causing horrific suffering to their hosts? Perhaps because something wicked designed them” (pp 219-220).

This is not science. This is an attempt to smuggle religion into the schools and devolve our understanding of life and ourselves back to the Iron Age.

If you want a more technical yet imminently approachable critique, I recommend Dennis McCarthy’s excellent response, Why Probability Zero Is Wrong About Evolution. As McCarthy puts it, Vox Day’s “best-selling anti-evolution book misuses mathematics and spreads misinformation.”

“Those who dwell among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

Rachel Carson

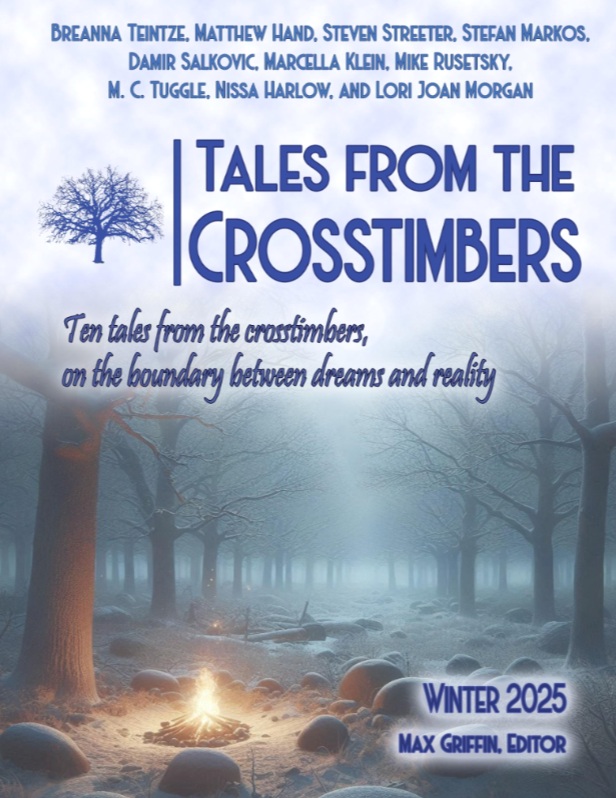

I’m pleased to announce that the winter issue of Tales from the Crosstimbers is now available on Amazon. It includes my story “At the Edge of the Crater.”

Jak, a newcomer to the mining colony on the asteroid 16 Psyche, ignores his partner’s warning not to travel alone into the asteroid’s Badlands. There’s a rich new vein of iridium to claim, and Jak wants first pick. All he has to do to win the race is to venture into a forbidding impact crater.

I wrote this tale as a futuristic version of “To Build a Fire” by Jack London. In “Crater,” the protagonist lets greed drown out the warnings of his more experienced partner. Space, like all of nature, often overwhelms us with its beauty and mystery but can also snuff out human life in an instant. To understand ourselves, and to grasp our place in the universe, we must realize we are mites compared to the limitless expanse of space. Survival is a struggle, one best waged with friends at our side.

Tales from the Crosstimbers features speculative tales “grounded in strong characters interacting with a gritty, realistic world.” So it’s the perfect venue for this story. I’m honored to be included with this line-up of authors.

Charles Darwin’s landmark book On the Origin of Species was first published on this date in 1859.

We haven’t been the same since.

As E. O. Wilson tells us, science provides “more solidly grounded answers” to life’s mysteries. Not only has the theory of evolution transformed science, it has also given us a powerful lens for examining ourselves. Sadly, we remain blind to Darwin’s foundational message, that humans are not invaders but a part of nature. This continued isolation from the natural world has dire consequences, as this recent article from Science Daily warns us:

“A new study by evolutionary anthropologists Colin Shaw (University of Zurich) and Daniel Longman (Loughborough University) argues that the pace of modern living has moved faster than human evolution can follow. According to their work, many chronic stress problems and a wide range of contemporary health concerns may stem from a mismatch between biology shaped in natural settings and the highly industrialized world people occupy today.

That means the mismatch between our evolved physiology and modern conditions is unlikely to resolve itself naturally. Instead, the researchers argue, societies need to mitigate these effects by rethinking their relationship with nature and designing healthier, more sustainable environments.”

What to do? We must recognize our relationship with nature. The places we live must be reimagined and revamped so they resemble our hunter-gatherer past. More green spaces, more walkways, less dependence on cars, more opportunities to see nature maturing and blossoming before us.

But the first, most essential step is to open our eyes and see what we truly are.

And now for something completely different: Poetry. Yes, it’s a new endeavor for me, a craft I’ve only dabbled in (such as this silly piece for the Charlotte Observer).

My poem “On the Train from Charlotte” is included in the latest Metaworker, a spunky little journal that has been featuring fiction and poetry since 2015. Here’s the magazine’s mission statement:

“Driven by passion, our fires are fanned by sharing engaging stories that aren’t afraid to put a spin on rules of craft, spit in the eye of convention, and provoke in ways that surprise, challenge, or enchant. We hope our readers leave the page with experiences that you can take back into your daily life, maybe even change a perspective you didn’t know you had.”

I hope “On the Train from Charlotte” affects you the same way.

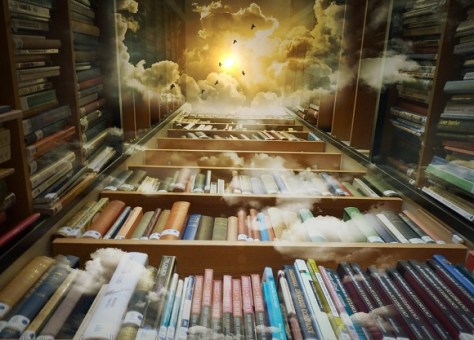

The latest findings on American literacy are troubling, and not just for educators and authors:

The number of Americans who read for pleasure has fallen by 40%, according to a new study.

Researchers at the University of Florida and University College London have found that between 2003 and 2023, daily reading for reasons other than work and study fell by about 3% each year.

Many causes contribute to this unsettling trend. More “how to” advice is presented in the form of videos rather than text. Often, when you’re trying to read a news story online, pop-up videos vie for your attention. Video games, with their numbing sound effects and over-the-top visuals, offer seductive, but mindless, distraction. How are books to compete?

And again, the effects are far-reaching. Written language is the bedrock of an advanced civilization. The wisdom of past generations boosts the available information to the present generation, freeing us from having to re-invent the wheel.

Just as important, language binds us to one another, helping us see ourselves in context. Reading stories opens our eyes, letting us see we’re not alone facing problems.

Finally, each of us is a story, a cohesive narrative that makes sense of our memories, good and bad, as well as our aspirations. Lacking that narrative, we fall apart. Little wonder so many people feel isolated, disconnected, not just from others, but from themselves. When children agonize about being born in the wrong body, they’re yearning for a cohesive identity, which helps define purpose.

A culture that actively promotes atomizing society into disjointed, isolated individuals needs medical attention. The humanizing power of language is just what the doctor ordered.

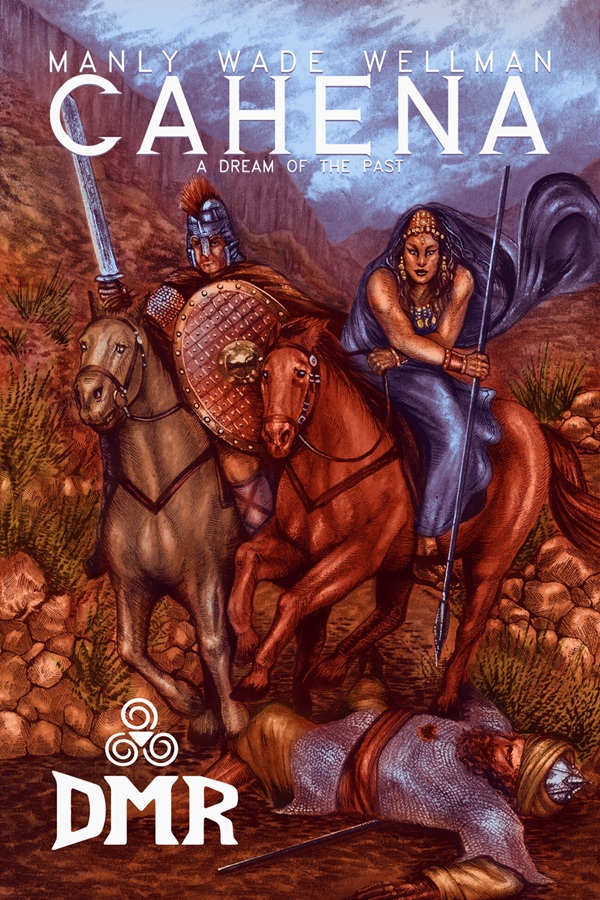

In his foreword to Cahena: A Dream of the Past, Manly Wade Wellman describes the last novel of his brilliant and prolific career as an historical novel. That’s mostly true. The book is rich in historical details, from the hardscrabble life of the Berbers to their preparations for battle, which are especially vivid and convincing. But this intriguing tale is also spiked with the sorcerous, including a demon that stalks the camps searching out doomed warriors, and a vampire.

The tale revolves around the military leader and enchantress known as the Cahena, who leads her people against invading Muslims from the east. The setting is north Africa around the beginning of the eighth century. The novel is told from the point of view of Wulf, a Saxon career soldier whose military prowess earns the Cahena’s trust, boosting him to the position of advisor and later her lover. The story moves smoothly and forcefully through military campaigns and romantic complications.

This book is a treasure to be enjoyed, from the gorgeous cover to the bittersweet conclusion. Brace yourself for realistic action, romance, betrayal, and heroism. History aficionados will especially appreciate the well-researched details of training and organizing an army. Call it historical fantasy, sword-and-sorcery, or historical romance, it delivers an entertaining, gripping tale.

Kudos to DMR Books for keeping Wellman’s legacy alive.