My hometown paper, The Charlotte Observer, has fired Kevin Siers, its Pulitzer-Prize winning political cartoonist. Like many other papers, the Observer has been whittling itself away the past few years. They lost their palatial office building, quit printing a Saturday edition, and have bled off numerous positions over the last decade: business editor, book editor, social editor, and so on.

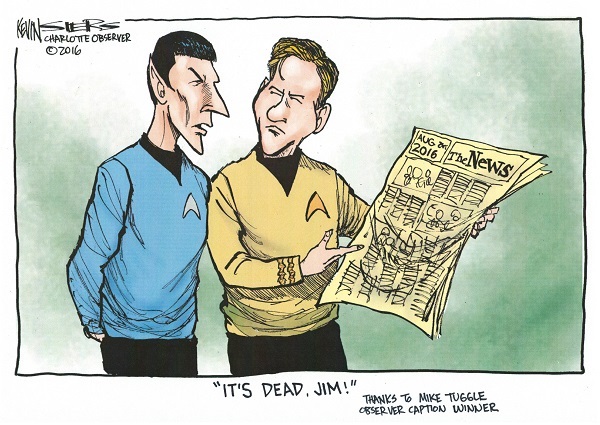

I didn’t agree with many of the Observer’s or Siers’ positions, but they were well presented and challenging. They used to host a limerick competition for St. Patrick’s Day and picked one of my limericks for publication. Kevin Siers picked my submission for his “Write that Caption” cartoon competition four times, and always awarded me with his original black-and-white drawing — except the last one, when he surprised me with the colorized version used for publication. (See above) It’s a cherished memento that now hangs framed in my office.

People tell me, “Just read the news online.” No. Trying to read online is not the same experience. Pop-up ads disrupt you. Worse, autoplay videos try to lure you away from the article, and videos aren’t as thought-provoking or enjoyable. Reading is an active and cooperative activity between reader and writer, while watching a video is passive and one-sided. Watching a video is like inserting electrodes into your brain and submissively absorbing the input.

Progress? This isn’t it.