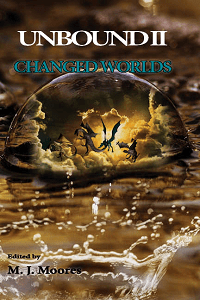

Award-winning DAOwen Publications has just released its latest anthology, Unbound II: Changed Worlds.

It features my story “Hunting Ground,” which is set in a brooding wetland in rural North Carolina. I grew up in the country, and the farm next to ours had a two-acre marsh where I stomped and rambled and dreamed away many an afternoon. It teemed with exotic plants, frogs, copperheads, and dark, mysterious pools. Now those were the days …

In my story, police discover the body of a fracking engineer buried near the marsh where he’d been working, and they arrest an anti-fracking activist who’d threatened him. Buddy Vuncannon, the defendant’s attorney, discovers the marsh hides a bizarre secret that could clear his client — if there were a way he could prove it in court.

My fascination with all things swampy and a Science Alert article about a mysterious stretch of land near Lake Michigan inspired the story. “Hunting Ground” is lively and entertaining, but its topic is serious. Fracking involves pumping a cocktail of chemicals and water deep underground where it cracks open layers of shale to unleash natural gas. The threat to the local water supply is profound.

Exposing the truth about fracking is all well and good, but the real goal is to renew respect and appreciation for nature. No one understands this better than poet/novelist/activist Wendell Berry. In his fiction and essays, Berry argues that the excesses of industrialism, from environmental piracy to the over-concentration of wealth, can be countered only by a rebirth of affection for the local, by which he means love and loyalty for the land we live on and for the people we live with.

Here’s how the National Endowment for the Humanities describes Berry’s literary/political mission:

In the debate that set Thomas Jefferson against Alexander Hamilton—and rural farms against cities, and agriculture against banking interests—Berry stands with Jefferson. He stands for local culture and the small family farmer, for yeoman virtues and an economic and political order that is modest enough for its actions and rationales to be discernible. Government, he believes, should take its sense of reality from the ground beneath our feet and from our connections with our fellow human beings.

And it is my passionate belief that one way we can strengthen or even restore those connections is through a good story. I hope you enjoy “Unbound II: Changed Worlds.”