Weapons hold a special place in all cultures. The tradition of a special bond between the weapon and its owner is one we see often in history, folklore, and literature. Think of the samurai’s katana, Thor’s Mjölnir, Arthur’s Excalibur, Bilbo’s Sting, and Davy Crockett’s Ol’ Betsy.

This morning, I attended a presentation at the Charlotte Museum of History on the Mecklenburg Longrifle, a fine and highly sought-after weapon produced here in the Charlotte, North Carolina, area in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Michael Briggs, the author of The Longrifle Makers of Guilford County and The Longrifle Makers of Forsyth County & Davidson County, displayed some breathtaking pieces from his personal collection, and generously identified and discussed longrifles that audience members brought in.

Author Michael Briggs examining a longrifle.

North Carolina had nine different schools, or regional styles, of longrifles. Those distinctive styles were the outgrowth of the culture of the settler population. The predominant Scots-Irish and German population in the North Carolina Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains brought their woodworking, silversmithing, and metalworking traditions together to craft elegant and vital weapons for life on the frontier.

Click to enlarge

What most fascinated me was the extraordinary detail and ornamentation gunsmiths imparted to their creations. These longrifles are truly works of art. When the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts featured a longrifle exhibit, the magazine ad announcing it featured a photo showing the gorgeous detail of an engraved silver stock with the motto “I’ve stopped people in their tracks without firing a shot.”

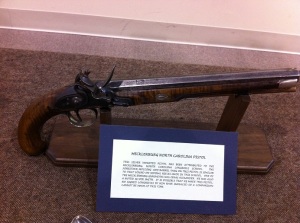

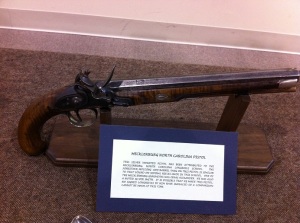

This pistol was the work of Zenas Alexander, who was also a noted silversmith working in Charlotte in the early 19th century. When Michael Briggs showed a photo of a silver pitcher by Alexander, someone behind me muttered, “Guns and tea sets. What a helluva combination!”

But I think there’s no disparity at all in Alexander’s dual careers. The longrifle was more than just a tool. It was necessary for hunting and self-defense. With it, a settler possessed security and independence. For the settlers on the North Carolina frontier, the longrifle was life itself. So the ornamentation wasn’t just an afterthought; it personalized the weapon. As the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts said, these guns were stunning works of art. And yes, they were weapons, too. Something that essential to life possesses a beauty of its own, and I think the extra effort Zenas Alexander and the other gunsmiths spent engraving their creations was their way of expressing the natural awe that the future owners of their creations would feel.

As John O’Donohue once said, “The human soul is hungry for beauty; we seek it everywhere – in landscape, music, art, clothes, furniture, gardening, companionship, love, religion, and in ourselves.” I’d add that beauty can be found where we often least expect it — and that makes it all the more compelling.