I can’t help but think of what Christmas will be like for the 14 families who lost loved ones in the San Bernardino massacre last week, or for the families of the three who were gunned down at the Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood facilities last month.

Even for those of us who were not immediately affected, there is still that haunting reminder of the needless suffering we, as humans, inflict on each other.

And yet — and yet — we should not let ourselves give in to despair. Tempted as we may be to concede that evil appears entrenched in the human heart, we cannot surrender our hope that there is a spark of good in everyone, a spark worth noticing and perhaps even cultivating as best we can. As hard as it is to imagine, I believe the shooters in both tragedies thought they acted for worthy reasons.

Robert Dear, Jr., the Colorado Springs killer, ranted in court, “I’m guilty. There’s no trial. I’m a warrior for the babies.” Twisted? Yes. Egomaniacal? No doubt. But even this murderer believed he was protecting the innocent and helpless.

As for Farook and Malik, we can only speculate that they considered themselves warriors for their faith. Nevertheless, whatever was churning through their minds when they abandoned their six-month-old baby and drove to the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health with two .223-caliber semi-automatic rifles and pipe bombs, their actions certainly warranted the swift and decisive response the SWAT team meted out.

That said, we cannot ignore the powerful forces that work on terrorists such as Dear, Malik, and Farook. Modern alienation devastates the isolated individual, and many dedicate themselves to what appears as a last, desperate effort to accomplish something significant and worthwhile. In his article, The Psychological Sources of Islamic Terrorism, Dr. Michael J. Mazarr of Georgetown University writes:

Mass technological life tranquilizes people, drains us of our authenticity, of our will and strength to live a fully realized life. The result of this process is alienation, frustration, and anger. A few themes stand out from this broad concept.

One has to do with the burdens of freedom and choice. By breaking the chains of tradition and conformity, modern life offers a bewildering, paralyzing degree of choice about everything from career paths to marriage partners to fashion. When you can potentially be anything, the existentialists worry, you may in fact be nothing — and have no identity at all.

Alienation from tradition and from others is not freedom, but a curse. In our frantic pursuit of material gain, we lose sight of life’s true purpose. No one has better enunciated the antidote than the protagonist of A Christmas Carol, that classic fantasy tale of Christmas. After the three spirits teach him what Christmas means, Ebenezer Scrooge makes his famous vow:

“I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach!” ― Charles Dickens, from his novella A Christmas Carol

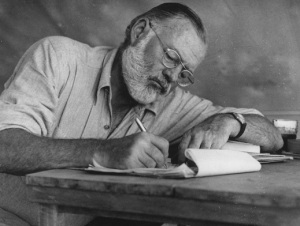

Stubbornly seeking the spark of good that’s buried even in the heart of old Ebenezer Scrooge gives us hope, real hope, because very often we do indeed find that spark if we simply open our eyes to it. That insight into human nature makes for better fiction, too. The best literature can be a means to form and strengthen social ties because it helps us appreciate the hidden feelings of others. In my novella Aztec Midnight, the protagonist, Jon Barrett, must find and deliver an ancient Aztec relic to men who have kidnapped his wife. However, a local militia stands in his way — not because its members are evil, but because the relic will empower the drug cartels that terrorize them. Jon Barrett’s dilemma is one we can all appreciate.

Want to help make Christmas the season of hope it was meant to be? You can start by reading a good book. Or better yet – by giving one.