Years ago, the opening scene of A Wizard of Earthsea captured my imagination and hooked me into this little classic. All who appreciate the power and beauty of words can’t help but feel the wonder Duny experiences as his gift for magic expands with his mastery of language. When his aunt, a witch, tells Duny the “true name” of falcons, he discovers this gives him control over them. This whets his appetite for more:

“When he found that the wild falcons stooped down to him from the wind when he summoned them by name, lighting with a thunder of wings on his wrist like the hunting-birds of a prince, then he hungered to know more such names. … To earn the words of power he did all the witch asked of him and learned of her all she taught, though not all of it was pleasant.” p. 5

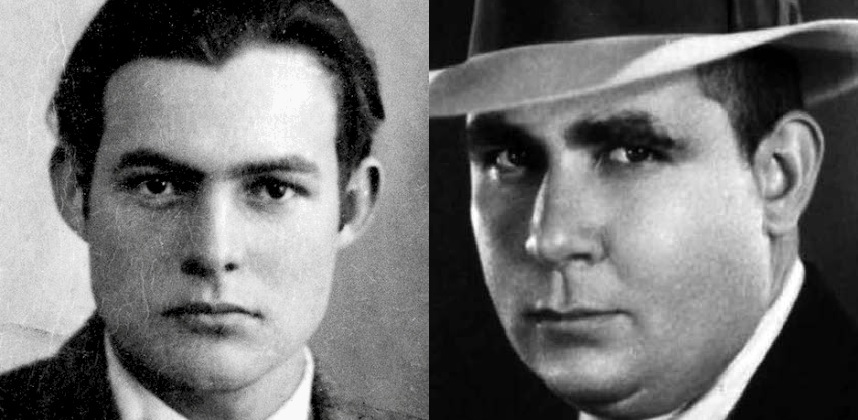

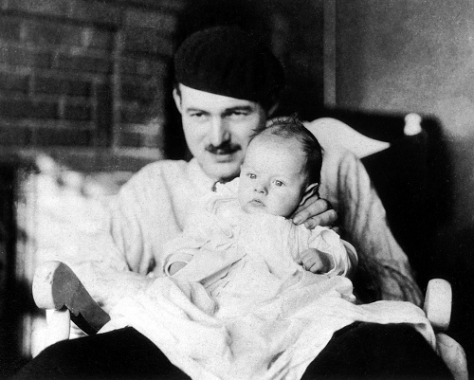

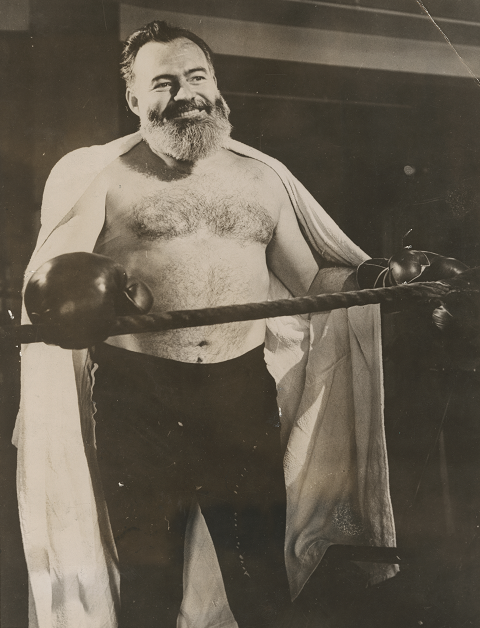

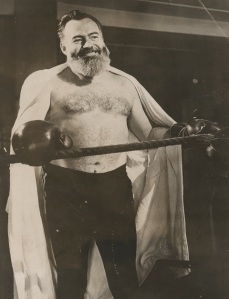

Ordinary mortals feel the same rush when they learn the names of things. My eyes always tear up when I watch the water scene from The Miracle Worker. Anyone who isn’t moved when young Helen Keller learns that words represent reality has a heart of stone. Leicester Hemingway wrote that by the time his brother Ernest was eight, he “knew the names of all the birds, all the trees, flowers, fish, and animals found in the Middle West.” Knowing the names of things connects you to them. It elevates and empowers you.

As beautiful as this truth is, it isn’t romanticism, but hard practicality. Faithful communication was our distant ancestors’ most important adaptation to a harsh environment, as Robert Ardrey illustrated in The Social Contract:

“The bipolar nature of hominid society … became the cradle of language as we know it. Things had to be told. A hunter was injured, a child was sick. Hunters returning empty-handed had to tell apologetically of the big one that got away. Leopards menacing the home-place had to be described by the women, numbered, placed on the map if the group was to be defended.” p. 327

That’s why telling the truth evolved into an ancient virtue. Lying not only disrupted social bonds, but also threatened survival. Accurate, truthful communication alerted one’s family and neighbors to both dangers and opportunities.

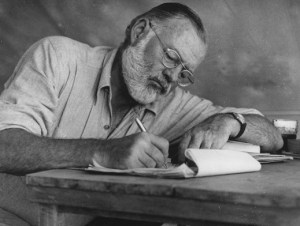

Modernity hasn’t changed this basic fact. Writers offer the world an ideal of precise transmission of ideas and emotions. That’s what Ernest Hemingway meant when he reminded himself that he had to write “the truest sentence that you know.” In other words, a writer must discipline himself to express his truth with conviction and stand by his words.

Clear, honest communication remains a goal for the individual and society. Ezra Pound once declared that “Good art cannot be immoral. By good art I mean art that bears true witness, I mean the art that is most precise.” Asked what he would do if he were governor, Pound’s mentor Confucius vowed to “rectify the names.” By “rectify,” he meant to restore, to purify, to correct, so that words would correspond to reality. That’s a discipline, an art, and a calling.