Well. Seems Joe Bob Briggs is torn these days. While repeatedly swearing his life long love for literature, he now claims it has no real-world value:

And eventually, if you study the data, which is what the Modern Language Association does, you have to reach the conclusion that studying English is good for…nothing. …

I’m racking my brain. I’m trying to come up with justifications. I’m trying to figure out some way this translates into “Yes, you are now prepared for life.” But alas, these modern students who thumb their noses at English are correct. It’s good for nothing. It has no practical value whatsoever.

Wait — NO practical value? C’mon, Joe!

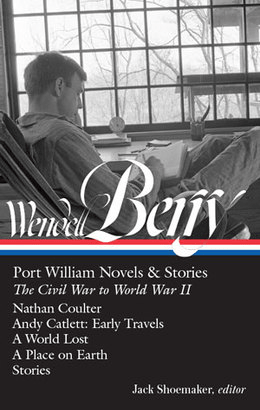

Briggs laments that many of today’s college students aren’t even considering majoring in English, and are instead flocking to more “practical” courses of study. No doubt a degree in accounting or math is more marketable these days. But to dismiss the study of literature as having no value is wrong, wrong, wrong.

We could argue that learning how to interpret complex texts has significant value in a technological world. We could talk about the crucial role of reading in improving one’s social intelligence, making one more adept at working with others, or how reading helps one form a robust and informed worldview to make sense of one’s place in the world. Or how fiction in general, and science fiction in particular, opens one to spiritual insights that can make you a happier, and therefore more productive person.

But if you insist on focusing only on hard science, we’ve got you covered. Scientists have solid evidence on the link between reading and general problem solving skills. The act of reading itself builds “white matter” in the brain that boosts its ability to recognize patterns and imagine new scenarios. The importance of reading in nurturing general intelligence is beyond dispute:

But in today’s world, fluid intelligence and reading generally go hand in hand. In fact, the increased emphasis on critical reading and writing skills in schools may partly explain why students perform, on average, about 20 points higher on IQ tests than in the early 20th century. The so-called Flynn effect is named after James Flynn, a New Zealand professor who has devoted much of his career to studying the worldwide phenomena of increasing IQ scores.

Knowing technical details is important, but developing the ability to use technical knowledge in new and creative ways is critical.