Sometimes otherwise smart people don’t stay in their lane. Trouble begins when they imagine they’ve discovered earth-shaking truths in fields unimagined by people trained in those fields. It’s called epistemic trespassing.

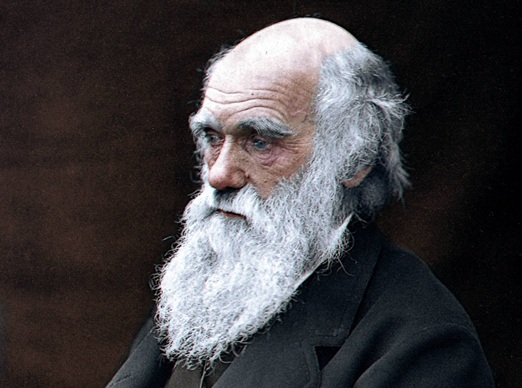

Ezra Pound revolutionized modern poetry but turned into a crank spouting bizarre economic theories. Linus Pauling won a Nobel Prize in chemistry before taking up quack medicine. Here’s the latest: Theodore Beale is an accomplished fantasy author who claims he’s destroyed Charles Darwin and natural selection. Writing under the name Vox Day, he’s released a book titled Probability Zero: The Mathematical Impossibility of Evolution by Natural Selection.

Here’s the description of his book from Amazon: “By subjecting the big ideas of Darwin, Haldane, Mayr, Kimura, and Dawkins to the pitiless light of statistical and mathematical analysis, Day demonstrates that the Modern Synthesis isn’t just flawed—it is absolutely impossible.”

And that’s it. Vox Day has made no ground-breaking research, no new discoveries, and offers no evidence from any science. He thinks he’s bypassed all that by claiming natural selection is so statistically improbable, it can be dismissed as impossible.

In other words, he only recycles the creationist “Junkyard tornado” argument that no scientific evidence can overcome the odds against life arising and developing naturally.

Okay. What would happen if we decided probability trumps evidence when making inquiries? I can “prove” it’s impossible my wife and I could have ever met and married. But a better example comes to mind.

Remember the horrific murder of Iryna Zarutska in Charlotte last August ? A lawyer could use statistics alone to shoot down the prosecution’s case against DeCarlos Brown Jr., who is accused of stabbing Zarutska on a late-night train.

Consider: Of the 8.3 billion people in the world, Brown allegedly murdered a woman born in Ukraine, 5,200 miles away. Every day on Earth, only 120 people are killed by strangers. That means the probability of a homeless man in Charlotte killing a woman from Ukraine is 0.00000144578313253 %. And since only 1.5 % of Charlotte residents use the light rail, the odds of Brown encountering and killing Zarutska would be reduced to practically nothing.

Should a jury ignore the so-called DNA and eyewitness evidence and let Brown roam the streets of Charlotte again? Hopefully, when DeCarlos Brown Jr. gets his day in court, the jury will judge him based on the evidence, which tells us that despite the odds, Zarutska was on that train when Brown killed her.

The theory of evolution is also backed by evidence–abundant evidence from many branches of science.

But here’s the kicker–Day doesn’t deny the evidence for evolution. He even cites an example of human evolution:

“The primary European lactase persistence allele (LCT-13910*T) is estimated to have arisen approximately 7,500–10,000 years ago, coinciding with the advent of dairying in Neolithic Europe. This mutation confers a significant nutritional advantage in cultures that practice animal husbandry, as it allows adults to digest milk—a rich source of calories, protein, fat, and calcium that would otherwise cause gastrointestinal distress” (p. 110).

If you’re puzzled, re-read the book’s subtitle: “The Mathematical Impossibility of Evolution by Natural Selection.” Creationists will be disappointed thinking the book is a refutation of evolution. So what is Day arguing? In the book’s foreword, Frank Tipler, a professor of mathematics, spells out its purpose: “Mr. Day will demonstrate that, since evolution cannot have occurred by unintended means, evolution must have been directed.” In other words, Day accepts the overwhelming evidence for evolution, but claims natural selection is not the cause.

Even though he doesn’t use the term, Day is arguing for Intelligent Design, a pseudoscience cobbled together as a front for creationism. ID emerged after the bad publicity following Edwards v. Aguillard, in which the Supreme Court ruled that teaching creationism is an unconstitutional attempt to establish a particular religion. While creationism argues that scripture justifies the belief that life was created by a divine being, ID co-opts large chunks of science in an attempt to assert some mysterious, unknown intelligence — maybe aliens! — created life. Day calls his version “Intelligent Genetic Manipulation.”

Like the old creationists, however, Day argues for a “First Mover” and “Designer” as the hidden driver of evolution and specifically posits the Abrahamic God as its guiding force. Addressing the argument that structural defects — the eye’s blind spots, for example — disprove intelligent design, Day offers this totally scientific explanation:

“perhaps demons might manipulate genetics in opposition to it, or for purposes of their own that align with neither divine nor human interests. This could explain certain puzzling features of biological design: not mere suboptimality, but apparent malevolence. Why do parasites exist that can only reproduce by causing horrific suffering to their hosts? Perhaps because something wicked designed them” (pp 219-220).

This is not science. This is an attempt to smuggle religion into the schools and devolve our understanding of life and ourselves back to the Iron Age.

If you want a more technical yet imminently approachable critique, I recommend Dennis McCarthy’s excellent response, Why Probability Zero Is Wrong About Evolution. As McCarthy puts it, Vox Day’s “best-selling anti-evolution book misuses mathematics and spreads misinformation.”