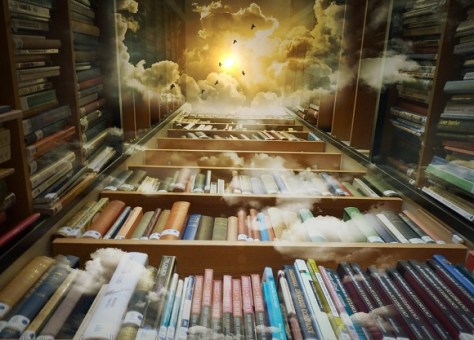

The latest findings on American literacy are troubling, and not just for educators and authors:

The number of Americans who read for pleasure has fallen by 40%, according to a new study.

Researchers at the University of Florida and University College London have found that between 2003 and 2023, daily reading for reasons other than work and study fell by about 3% each year.

Many causes contribute to this unsettling trend. More “how to” advice is presented in the form of videos rather than text. Often, when you’re trying to read a news story online, pop-up videos vie for your attention. Video games, with their numbing sound effects and over-the-top visuals, offer seductive, but mindless, distraction. How are books to compete?

And again, the effects are far-reaching. Written language is the bedrock of an advanced civilization. The wisdom of past generations boosts the available information to the present generation, freeing us from having to re-invent the wheel.

Just as important, language binds us to one another, helping us see ourselves in context. Reading stories opens our eyes, letting us see we’re not alone facing problems.

Finally, each of us is a story, a cohesive narrative that makes sense of our memories, good and bad, as well as our aspirations. Lacking that narrative, we fall apart. Little wonder so many people feel isolated, disconnected, not just from others, but from themselves. When children agonize about being born in the wrong body, they’re yearning for a cohesive identity, which helps define purpose.

A culture that actively promotes atomizing society into disjointed, isolated individuals needs medical attention. The humanizing power of language is just what the doctor ordered.