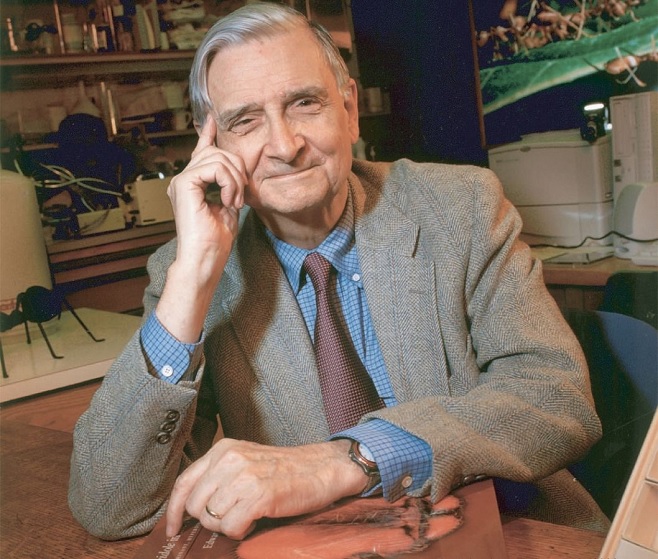

“Much of good science — and perhaps all of great science — has its roots in fantasy.”

E. O. Wilson, Letters to a Young Scientist

“Much of good science — and perhaps all of great science — has its roots in fantasy.”

E. O. Wilson, Letters to a Young Scientist

I’m happy to see that more publishers won’t accept works created by AI. For the life of me, I can’t understand why someone would stick their name in the byline of something created by a computer program, but after all, plagiarism is nothing new. If people will take credit for something somebody else wrote, why not claim an AI product?

This issue isn’t going away. In Ray Kurzweil’s latest book, The Singularity is Nearer: When We Merge with AI, he claims AI will match and even surpass the writing of the best authors. These programs, he argues, will be “familiar with virtually every kind of human writing. Users could prompt it to answer questions about any given subject in a huge variety of styles — from scientific writing to children’s books, poetry, or sitcom scripts. It could even imitate specific writers, living or dead.”

Can it? I don’t think so. Ray Kurzweil is a transhumanist who advocates merging humans with AI as well as enhancing human ability with genetic engineering. Kurzweil believes we can upload our minds to a computer and live forever. Transhumanism despises the body, traditional culture, and humanity in general. Worse, it doesn’t understand any of the things it wants to replace.

First of all, human beings are not ghosts in a machine. The notion that our minds ride around in a meat robot that can be ditched without changing who we are is hopelessly simplistic. What we call the mind is the sum of the functions of the brain, which is a physical organ. And the brain interacts with the rest of the body. In fact, the field of Embodied Cognition tells us the body is central to our thought processes.

There’s solid research to back this view. Mirror neurons fire when we perform an action or when we observe someone else performing that action. Embodied Cognition also tells us that language is metaphor, and the building blocks of metaphor are physical sensations. Magnetic resonance imaging scanners reveal that when we read about a physical action, we activate the same areas of our brains as when we actually perform those actions. That’s the mirror neurons at work.

The bottom line is that disembodied machines cannot think, feel, or write the way humans do. And never will.

There’s a powerful and alluring line in Haruki Murakami’s novel Norwegian Wood I’ve always loved: “I don’t want to waste valuable time reading any book that has not had the baptism of time.”

The character meant that in a limited sense; he felt only old books that had endured for generations were worth reading. But I would add that works that acknowledge and explore the deep and often inscrutable influence of the past are also “baptized of time” and make the most moving and inspirational reading. William Faulkner captured that insight perfectly in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.”

I’ve long believed the healing power of literature rises from its ability to let us see our deep connections to others, the world around us, and the cosmos. Rachel Carson once wrote that “To understand the living present, and the promise of the future, it is necessary to remember the past.”

Growing up around Civil War and American Indian sites, I absorbed a deep appreciation of the past, and that is reflected in the stories I write. My latest is “Making a Ton,” featured in the Minstrels in the Galaxy anthology, The protagonist, a pilot in the Asteroid Belt, reflects on his connections to the trailblazers who led humanity into space:

Ray stepped towards the window. “We got to this moon on the shoulders of giants,” he announced. “Pioneers, heroes, every one of them. Giving up would be an insult to their memory. They were men and women who roared into space in ships powered by chemical fuel that could’ve exploded and turned them to space dust. But they did it anyway. They were people with backbones, muscles, and scars, and courage. That’s what space travel is about, not technology. I feel like I’m with them when I’m piloting.”

Riveting adventures, echoes of lives lived well, and guideposts for discovering what makes us what we are — that’s the goal of all good stories.

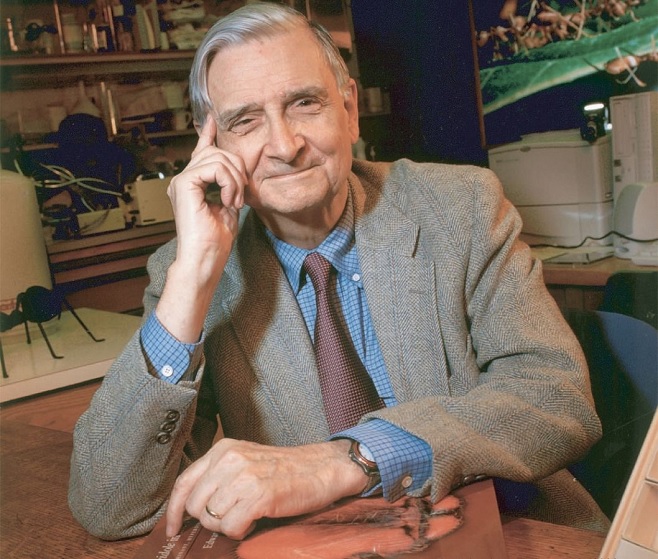

“The truth is always revolutionary.” Tom Wolfe

Alpha Mercs has published Minstrels in the Galaxy, their latest anthology, and I’m pleased to say it includes my story “Making a Ton.” Editor Sam Robb was very kind in his acceptance letter: “Loved your story. Definite Larry Niven / Known Space vibes.”

The music of Jethro Tull is the theme for this unique anthology of twelve romping tales. I’ve always loved “Too Old to Rock ‘n’ Roll: Too Young to Die!” so it was a natural choice for my story “Making a Ton.”

And that cover art is truly a thing of beauty. Cedar Sanderson outdid herself.

The action in my piece unfolds at an ice mine on Saturn’s frozen moon Enceladus. (Yes, I’ve been there before. I find Enceladus endlessly fascinating.) Ray, an aging pilot who can’t find work, bets his life savings on a race against an alien who not only has a state-of-the-art ship, but an inborn talent for speeding through the Asteroid Belt.

What is Ray thinking? Does he plan to go out with a bang? Could this be the final take?

There’s only one way to find out.

Available on Amazon in Kindle or paperback.

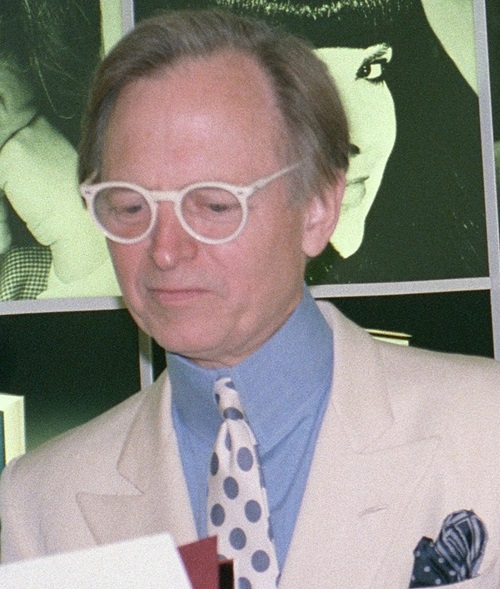

In Another Time Magazine has published my short story “Workforce Reduction.” In her acceptance letter, editor Agatha Grimke wrote, “This was very well written and a fun piece, and we really liked the way you told the story through executive emails.”

Thank you, Agatha! This is my first shot at epistolary fiction, and it was a blast to research and write. Not sure how you’d classify it — dark sci-fi? satire? Whatever you call it, I was extremely pleased how my observations on religion and current events dovetailed into the story arc.

“Workforce Reduction” draws on my days working in Organizational Development for an insurance company, where I analyzed workflow and designed new procedures. That’s where I first learned about Dr. Jerry Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy. In addition to being a science fiction author, Pournelle was an influential OD scientist. His Iron Law says, “In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control.”

In other words, bureaucracies tend to become self-serving. I can attest to the accuracy of that law. Boy, can I ever. My story features creepy aliens and back-stabbing bosses, but Pournelle’s law is the real antagonist in this story.

Available now on Amazon in Kindle or paperback.

So thrilled to see my story Only You and I Together published at White Cat Publications. Kay DiBianca, the award-winning author of Time After Tyme, read it and commented, “Very moving.”

The inspiration for this story hit me when my brother and his wife joined me and Julie at the beach, the first opportunity we’ve had in years to spend a week together. We both commented on traits we saw in each other that reminded us of our departed father. Dad’s voice, mannerisms, and wry humor filled a room overlooking the ocean once again, recalling family vacations from long ago.

Later, it dawned on me that the two of us, in a way, had made our father come alive. So this is a story I put my heart into. I still get a little misty when I read it.

The title? I borrowed that from The Waste Land, which is fitting inspiration:

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

My father witnessed the horror of war and death, and struggled the rest of his life to overcome PTSD. Despite that all-but-consuming torment, he made himself into a loving husband and father. He was the most decent man I have ever known. This story is for him.

“Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual.”

Carl Sagan