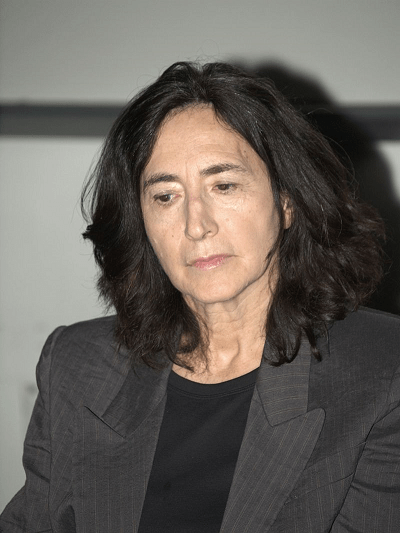

“‘Centrism’ is about eclecticism across time, not just across the partisan spectrum: I’m a ‘reactionary’ about some civilizational traditions that proved useful for centuries, but a ‘progressive’ about embracing many social & technological innovations.” Dr. Geoffrey Miller, evolutionary psychologist

“‘Centrism’ is about eclecticism across time, not just across the partisan spectrum: I’m a ‘reactionary’ about some civilizational traditions that proved useful for centuries, but a ‘progressive’ about embracing many social & technological innovations.” Dr. Geoffrey Miller, evolutionary psychologist

Where the Western Meets Crime Fiction

John Larison argues that despite the different tropes they use and the different worlds they occupy, crime and Western stories share many structural similarities:

John Larison argues that despite the different tropes they use and the different worlds they occupy, crime and Western stories share many structural similarities:

Both are about the triumph of good over evil. Early in a novel of either genre, we will see our protagonist encounter an injustice, usually the victim of crime (who may or may not still be breathing). Both novels will end when the scales of justice have finally been righted; the perpetrators of evil have met their due punishment. In a crime novel, justice usually comes in the form of a court of law. In the western, justice tends to be delivered by a bullet through the heart.

That’s a good start, but there’s more substance, nuance, and grit in both genres. Crime fiction includes many sub-genres, including cozies (Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple tales) and classic whodunits (Ellery Queen). The reader can settle down with one of these books knowing that justice will inevitably prevail, just like in the Westerns. But then there are hardboiled and noir crime stories. While both feature violence in gritty, naturalistic settings, only hardboiled tales come close to the worldview of classic Western adventures.

In hardboiled crime tales, the protagonist shoots it out with the bad guys to protect the innocent and restore justice. Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer is an updated John Wayne battling the bad hombres of New York City. However, in noir tales, traditional justice is just as hard to find as an innocent victim. For example, Raymond Chandler paints a bleak view of human nature in his novels, with both the criminal underworld and the “respectable” upper class up to no good. In such a world, the protagonist has to settle for upholding his personal code of honor, justice for the innocent proving too elusive, if not illusory.

Some of the “crime-westerns” Larison cites in his article certainly don’t end with the good guy riding into the sunset after protecting the righteous and punishing the wicked. Just to name one example, Cormac McCarthy’s “No Country For Old Men” ends with the bad guy, a sociopathic hit man, virtually unscathed and free, leaving behind the corpses of almost all the sympathetic characters. The sheriff who failed to catch the killer or protect the innocent acknowledges his uselessness at the end, and dreads the evil that’s spreading across the land he once loved and knew. Not exactly “Shane.” But, as Larison says, still wildly entertaining.

This day in history

H. P. Lovecraft was born on this date in Providence, Rhode Island. A self-taught science and astronomy buff, Lovecraft built upon the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe to pioneer and define what is now known as weird fiction and cosmic horror.

H. P. Lovecraft was born on this date in Providence, Rhode Island. A self-taught science and astronomy buff, Lovecraft built upon the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe to pioneer and define what is now known as weird fiction and cosmic horror.

In addition to his many works of fiction, he was a prolific correspondent, notably with Robert E. Howard. His works continue to inspire both writers and moviemakers. Writers who acknowledge Lovecraft’s influence include China Miéville and Joyce Carol Oates. Lovecraft has also inspired indie filmmakers Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead, as well as Guillermo del Toro.

This day in history

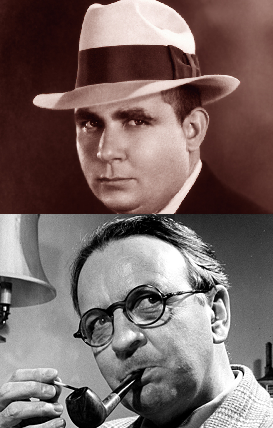

Chandler and Howard

Raymond Chandler and Robert E. Howard had a lot in common, and I think acknowledging and appreciating their similarities help us to better understand and enjoy their thought-provoking works.

Both were successful pulp writers who are now viewed with much more respect than they were when they worked and lived. Chandler’s novels are now taught at the university level, and many writers cite Howard as a key influence. Stephen King, for example, once declared that “Howard was the Thomas Wolfe of fantasy.”

Chandler and Howard revolutionized their respective genres by energizing them with a stark, naturalistic picture of human nature and society. Not only were their stories more gritty and violent than what most of their predecessors wrote, they also injected grim views of society into their tales. Chandler’s Los Angeles is a hopeless, irredeemable jungle. In The Long Goodbye, he paints a bleak picture of the city’s upper class, which is just as prone to criminality as the lower classes. Howard, in Red Nails, imagines a dying city whose few survivors, despite their wealth and learning, wage an unrelenting and mutually destructive blood feud on each other.

The wild 1920s and desperate, corrupt 1930s shaped the world views of both writers. When Raymond Chandler moved to Los Angeles, it was a boom town whose explosive growth was fueled by Hollywood and the oil industry. He worked for the Dabney Oil Syndicate, where he got an eyeful of the dirty dealing and outright corruption in both the oil business and local politics. Robert E. Howard also witnessed the suffering and debauchery inflicted on men and women in oil boomtowns throughout Texas. He once confessed to one of his editors, “I’ll say one thing about an oil boom; it will teach a kid that Life’s a pretty rotten thing as quick as anything I can think of.”

Raymond Chandler’s most famous creation, detective Philip Marlowe, is a hardened, clear-eyed fighter who nevertheless will stick his neck out for the helpless. Marlowe repeatedly saves the drunkard Terry Lennox on several occasions in The Long Goodbye, despite the trouble Lennox always brings to those who get too close to him. Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian, though a ferocious brawler and swordsman out to make a fortune any way he can, including stealing and working as a mercenary, often risks his life to help others. While wandering lost in a deadly and perverted maze of demons and monsters in The Scarlet Citadel, Conan hears a piteous moaning, and “the suffering of the captive touched Conan’s wayward and impulsive heart.”

The tragic element in Conan and Marlowe is that both characters uphold a personal code of honor despite the hostility and unconcern of the outside world. That, plus crisp, forceful writing, makes their otherwise bleak adventures so endlessly fascinating and re-readable.

Tolkien was right!

Tolkien was right about quite a few important topics. Scientists now know he was also right about the complexity and interconnectedness of our cousins the trees. From Collective Evolution.

A Quiet Place

As my wife and I settled into our dollar-movie-theatre seats, I was pleased to recall that yet another sci-fi film had received glowing audience and critical acclaim. Minutes after it started, I realized the reviews don’t give a clue about how good, how intelligent, and how soul-stirring this movie is.

Yes, it’s entertaining, and yes, it breaks conventions. Some of the breaks worked for me. Making it a (mostly) silent movie transformed it into much more that a “scary” movie. And scary it is, with plenty of white-knuckle scenes as a rural family cowers from a blind but ruthless predator that locates and attacks its victims when they make the faintest sound. The scant dialogue revved up the power of the visual tension to nearly unbearable levels. (At one point, a lady a few seats behind me whispered to her husband that she couldn’t take any more, and scampered out of the theatre.) Some of the conventions it broke left me feeling a bit cheated and shocked. Think a tale about a loving family struggling to survive will end without any casualties? The movie breaks that one in the first scene.

So it’s a hard film to watch at times. But “A Quiet Place” is a masterpiece of cinematic storytelling. Also, it tackles some themes head on in ways I found deeply moving and agreeable. It’s a pro-natalist, pro-sociobiology adventure; both the mother and father courageously do what they must to preserve the family. Despite the danger and the sacrifice, the husband and wife decide to have another baby. (And remember – babies cry!) At one point, the mother asks her husband, “Who are we if we can’t protect our children?”

That’s the key question of our age – just as it is in any age.

Learning to see

Ursula Le Guin once told a class of aspiring writers, “We are the raw nerve of the universe. Our job is to go out and feel things for people, then to come back and tell them how it feels to be alive. Because they are numb. Because we have forgotten. We have forgotten our rituals. Our tribal practices. There is no more tribe. We don’t know how to tell our elders our dreams around the morning fire. There is no morning fire. We can’t receive insight from the mothers.”

That is the writer’s goal, to reawaken others to what it means to be human in an age that’s severed us from nature, memory, and connections. If we’re to tell others how it feels to be alive, we must first feel it ourselves. No doubt writers, like other artists, pursue their craft because they naturally notice details and patterns their friends often miss, and want to express their insights to others. But just as we constantly improve our craft, we must also hone our senses.

I’ve found that physical exercise, especially martial arts, is an effective way to sharpen the senses and unify mind and body. But if you’re unable to make it to the gym or dojo, there are alternatives. In 10 Tests, Exercises, and Games to Heighten Your Senses and Situational Awareness, Brett and Kate McKay offer some excellent resources to boost your powers of perception.

I was especially impressed by the McKays’ comments about the different roles of the senses in experiencing the world around us. Writers should be aware of how our senses inform us about our surroundings and arouse certain emotions. For example, while sight is vital, our sense of hearing is wired more directly to the primal areas of the brain, and therefore trigger emotional responses more directly and profoundly. Smell and taste stir both emotions and long-term memories — Marcel Proust’s madeleine episode from Swann’s Way is one famous literary example.

So when we translate our impressions of the world in our writing, we should take advantage of as many senses as possible to make our stories more realistic, believable, and enjoyable.

What Is a Southern Writer, Anyway?

Writing in the New York Times, Margaret Renkl grapples with the nature and resilience of the Southern literary tradition. Not only does Southern literature claim such past greats as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty, but modern-day Southern writers, such as Wendell Berry, Ron Rash, and Ann Patchett, who continue to build on that tradition. How can this be, Renkl asks, in a region that is undergoing such profound changes? Her conclusion is worth considering:

It has all made me wonder: What if being a Southern writer has nothing to do with rural tropes or lyrical prose or a lush landscape or humid heat so thick it’s hard to breathe? What if being a Southern writer is foremost a matter of growing up in a deeply troubled place and yet finding it somehow impossible to leave? Of seeing clearly the failings of home and nevertheless refusing to flee? … Maybe being a Southern writer is only a matter of loving a damaged and damaging place, of loving its flawed and beautiful people, so much that you have to stay there, observing and recording and believing, against all odds, that one day it will finally live up to the promise of its own good heart.

Much has been said about how art often arises from pain, something the South has known all too well. Sometimes, suffering can lead to insights not obvious to those who have evaded bad times. In addition to such recurring themes as the joys and anguish of family, history, and nature, Southern literature often questions the triumphalism and confidence in progress seen in the works of Northern writers. And yet, Southerners love their heroes, characters who press on despite the odds, as well as tales of glory and derring-do. Robert E. Howard’s stories are well-known for both their pessimism about progress and their celebration of courage in desperate situations.

I’d argue that the chief attraction of Southern writing is the genre’s celebration of the human ability to stagger to one’s feet after disaster and relish the beauty and mystery of life despite it all. As William Faulkner wrote in The Sound and The Fury, “Wonder. Go on and wonder.” Good advice.

Quote of the day

“In order to be clear it is necessary to at least consider the possibility that we actually may not be. It requires stepping outside of one’s self, reading a sentence as if we were another person (not us) who didn’t understand, and even sort of admire the newly minted gold on the screen or the page. It requires a kind of humility, an ability not to take everything personally and to separate ourselves from our work. Clarity is not only a literary quality but a spiritual one, involving, as it does, compassion for the reader.” Francine Prose

For more thoughts on the social value of literature, see here and here.